XXXXIII. The Ancient Transformative Power of Writing

Let this observation be a safeguard against sinning.

Dear reader, the 25% Black Friday discount for this publication ends tomorrow.

“The struggle is great, the task divine — to gain mastery, freedom, happiness, and tranquility.” — Epictetus

Do you enjoy the Stoic works — the comfort and encouragement they provide?

I have some bad news for you.

Reading Stoicism is a great first step to improving our rational powers.

But it’s only the first level in making progress.

To gain more we must create our own wisdom, extrapolate lessons from ordinary life experiences, teach others.

We have to become our philosophy.

“Your mind will come to resemble your frequently repeated thoughts, because it takes on the hue of its thoughts.

Dye your mind, then, with a succession of ideas such as the following:

Wherever it’s possible to live, it’s possible to live well.” — Marcus Aurelius

Why put ourselves through all that labor?

For a great and illustrious life full of — wealth and friends, freedom, happiness, peace, and power.

You owe yourself this liberty and security.

Your loved ones will value and thank you.

Still in doubt on why you ought to go all in on Stoicism?

Read my essays on the Will to Power and Strength equals Ease to discover why it’s in your best interest to become a Stoic.

Today I’ll teach you how to get the most out of this publication and what you will or have read on your own.

I used the methods I’ll be recommending to synthesize and integrate hard concepts back in medical school.

It's what helped me learn faster, remember what I learned, get better at the art of diagnosing my patients, and manage them well resulting in better outcomes.

We’ll draw from those medical school principles for our Stoic training to become the great people we were meant to be, better partners, parents, work-men, enjoyers of life, conquerors.

The first way was to read about an illness from a medical resource then go to the hospital wards, get a patient with the same illness, take a detailed history, and perform a thorough examination on them.

The other way was to sit by my study table and pick an illness or topic from my long to-do list.

I’d then ask myself about its ontology: definition, epidemiology, etiology, pathophysiology, clinical features, diagnosis, treatment, complications, and prevention — without consulting a medical resource.

After I was done I'd crack open a medical book or a peer-reviewed online resource and see what I missed in my exposition.

I’d also take time to hear the histories my friends took from their patients and critique the technique they used, point out what they missed, or show them an easy way to collect quality information to aid in diagnosis.

They’d get better.

In turn, I’d improve because good technique was always circulating my mind, in progress to crystallization.

We’ll apply the same rigorous techniques to integrate the art of living.

How?

Michel Foucault tells us in his essay on self-writing that,

“To write plays the role of a companion by giving rise to the fear of disapproval and to shame.”

…

“By bringing to light the impulses of thought, it dispels the darkness where the enemy's plots are hatched.”

The methodologies of transformative writing I’m about to prescribe were popular with the greats like Napoleon Bonaparte, Thomas Jefferson, Montaigne, Marcus Aurelius, Seneca, Pythagoras, and Plutarch to cultivate a fertile nidus of lofty thoughts and a greatness of soul.

Athanasius, the writer of the Vita Antonii endorses this practice by telling us,

“Let this observation be a safeguard against sinning.

Let us each note and write down our actions and impulses of the soul as though we were to report them to each other.

And you may rest assured that from utter shame of becoming known we shall stop sinning and entertaining sinful thoughts altogether.

Who, having sinned, would not choose to lie, hoping to escape detection?

Just as we would not give ourselves to lust within sight of each other, so if we were to write down our thoughts as if telling them to each other, we shall so much the more guard ourselves against foul thoughts for shame of being known.

Now, then, let the written account stand for the eyes of our fellow ascetics, so that blush-ing at writing the same as if we were actually seen, we may never ponder evil.

Molding ourselves in this way, we shall be able to bring our body into subjection, to please the Lord and to trample under foot the machinations of the Enemy."

Now, let’s tap into the power of self-writing through the following two methods.

P.S: Take your practice with a bit of seriousness, while having fun with it. That’s all I ask of my readers.

You’ll also be wise to make self-writing a habit because,

“No technique, no professional skill can be acquired without exercise;

nor can the art of living, the tekhné tou biou, be learned without an

askésis that should be understood as a training of the self by oneself.”

Let’s get into it.

1. Hupomnémata

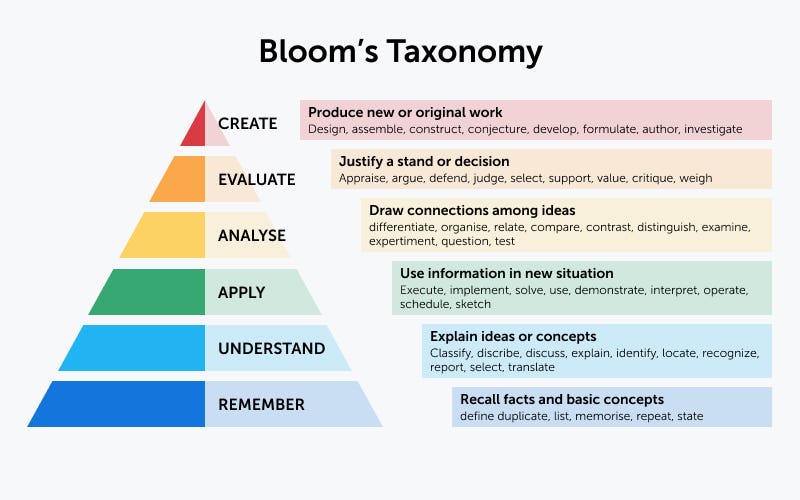

Self-writing is in line with Bloom’s taxonomy as illustrated in the diagram below.

Hupomnémata is whereby we use a physical journal (most recommended), or an online one to note down our favorite thought-provoking quotes, passages, examples, case studies, and admirable actions we’ve read, seen, or heard.

It’s how we own the lessons we’ve picked up by thoroughly digesting them and meditating on how they can apply to our lives.

Having this commonplace book helps us rekindle and refresh lessons from salient meditations on the art of living so that we don’t lose our way.

It helps us get back on track when we’ve slipped up.

Like the chronically ill invalids, we don’t get better with one dosage of a prescription — philosophy bids us to make living well a practice we honor.

We also get to have better solutions for the problems we’re dealing with because we have great templates from people who dealt with the same issues.

These accounts help us deal with jealousy, envy, anxiety, lust, anger, loss, an inferiority complex, love, poverty — anything.

Remembering isn’t the aim of hupomnémata.

The goal is to inform rational action.

“Get over your thirst for books, so that you don’t die grumbling, but with true serenity and with heartfelt gratitude to the gods.” — Marcus Aurelius

Michel Foucault tells us the practice of reading, re-reading, and writing transforms us because of these two important reasons:

“the regular practice of the disparate that determines choices1,

and the appropriation which that practice brings about2.”

Refining our judgments and then becoming an embodiment of our principles is what creates the canyon between the real practitioners and the quote spitters who might know all the words from the Stoic texts and are quick to correct us when we misquote them, but their lives are still miserable.

A key measure of progress here is if we’re able to use our training when we get tested, gauging our actions through the following metrics:

Do you like this meditation so far? ⭐️

Support the publication to read the rest and access 100+ premium essays & meditations.

Here’s what other readers are saying…